Overview

A millennia of innovation +

an abundance of resources =

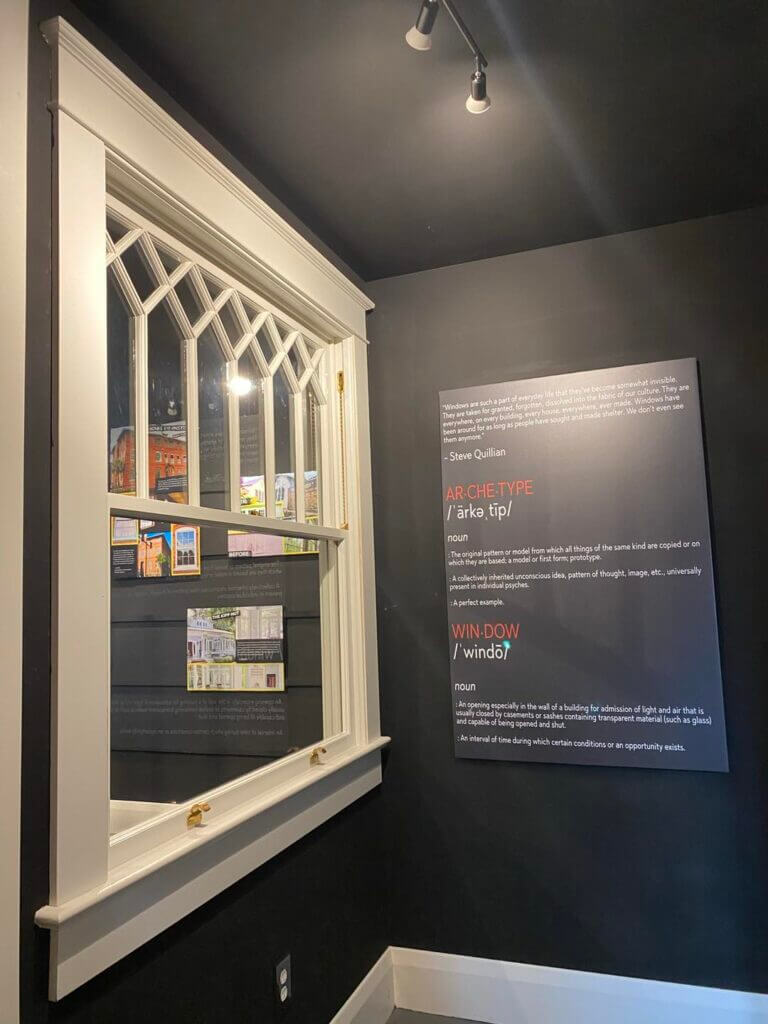

The Archetypal Window

1870’s America saw the most significant advances in window making ever seen. Glass manufacturers had mastered the mass-production of glass, there was an ‘endless’ supply of trees, metalworking had been mastered, and trains made widespread distribution a reality.

Up until that time, window making emerged and evolved alongside people with great difficulty over a very long period of time. It took an enormous amount of effort to make a good window.

All goods were made by hand, and by people. They were built to get the most value for the longest period of time. The long-term value of the product had to be greater than the effort it took to make it.

True innovation is hard and usually takes place over a long period of time, working out one design flaw at a time.

By the 1920s, people had figured out how to make the most practical, easy to assemble, maintainable, repairable, longest lasting, best functioning window ever made. These were windows only royalty could afford, just one hundred years before.

Humanity invented, over thousands of years, the archetypal window. And they were made so well, that many of them are still with us today.

Anatomy of a Double-Hung Window

Double hung windows as we know them today were developed in the United Kingdom and moved over to the United States through colonization.

Double hung windows contain two sashes that overlap and can move up and down in the window frame.

Counterweights held in boxes on either side of the window are used to support the sashes, and enable them to glide open or closed.

Double hung windows are an efficient type of windows because both the top and bottom sashes move.

Many older buildings in warmer climates contain double hung windows because they are easy to clean and maintain and because they allow airflow.

Opening both the top and bottom sashes by equal amounts allows warm air to escape through the top which pulls in cool air from outside through the bottom.

History

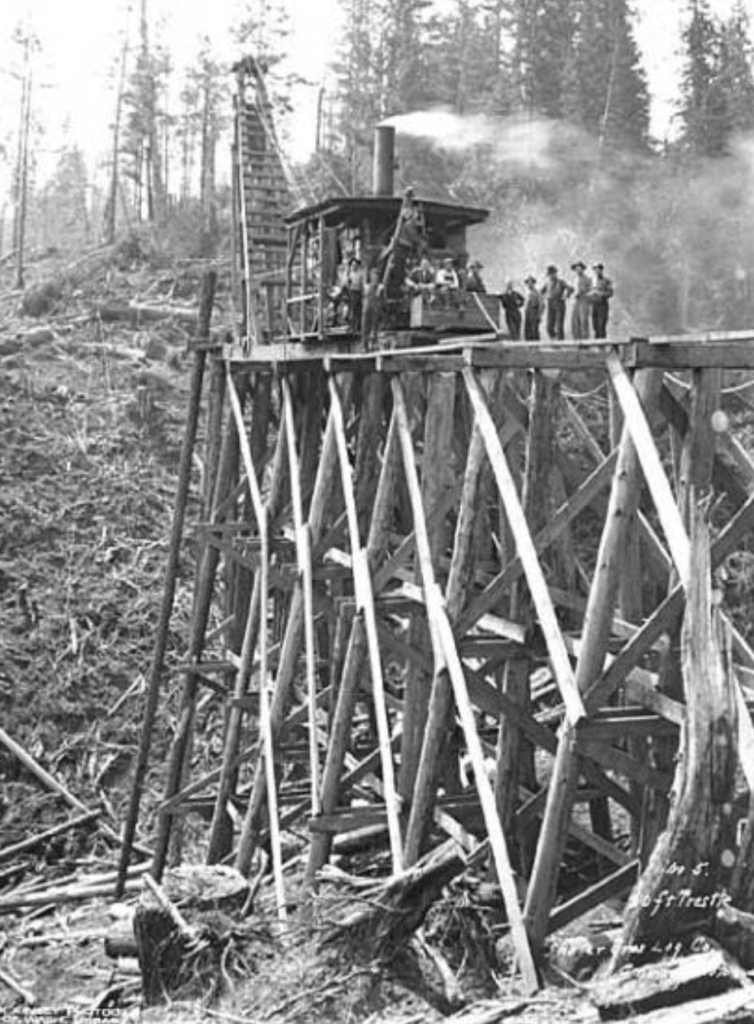

There was a confluence of four major industries that made this “universal” window possible.

First, it was lumber. Lumber was the foundation and basis of the early economy in the United States. Second, it was steel. The abundance of lumber ignited the growth of the steel industry, which led to the third industry, transportation.

Transportation—the convergence of wood and steel made the railroads possible and it actually more wood than steel to make train transportation possible. Think about the tracks that are laid—what’s underneath the steel tracks? Trees. Transportation led to the last of the converging industries—glass.

Before, because of its fragile nature, glass production was isolated to individual communities.

Transportation via railroad made it possible to grow the glass industry to a massive scale, and ironically it was standardization in the glass industry that led to standardization in the window industry—glass was sized in 2 inch increments shipped in cases. Windows were built around these sizes.

The windows built during this era were fashioned after the design that took thousands of years to refine.

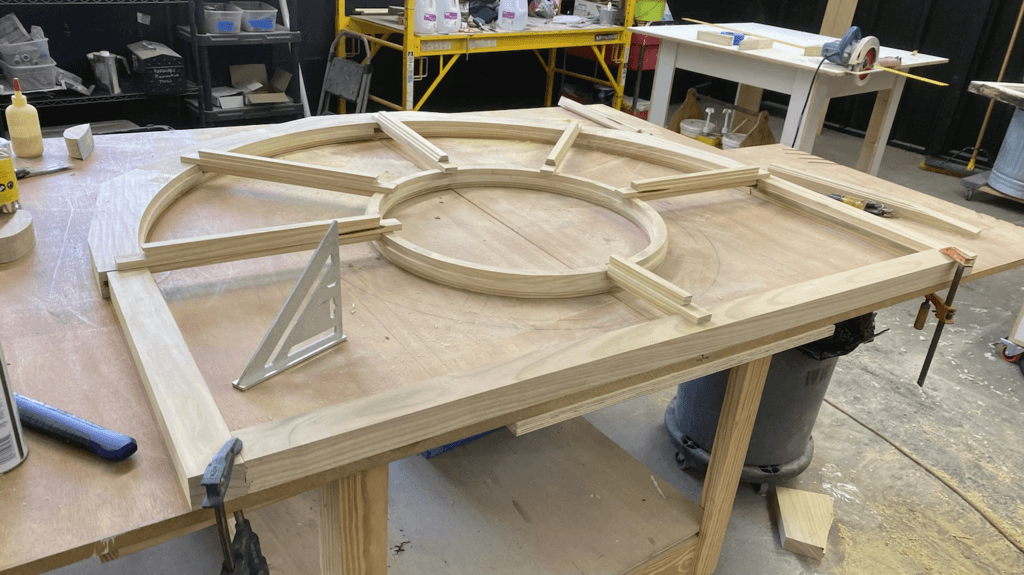

It is a design that is, to date, the one most in alignment with nature, longest lasting and universally serviceable. It is a design that emerged through struggle. To make a window, trees needed to be hewn by hand, logs split, seasoned and dried for a time until they could be milled into their individual parts, which again were made by hand.

Artisans thought in terms of perpetuality, the work was too hard to waste movements or to assemble items thoughtlessly. “If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing well” could have been a mantra of the time.

Over time all the design flaws were worked out. Anything unnecessary was eliminated.

What was left was a design that is still referenced today in practically all modern window design. It is this design, a design that has its roots based in struggle, that was taken and made at scale and sent universally across America and elsewhere. It’s why it has lasted so long and is still here.

This is why I term this turn of the century window “THE ARCHETYPAL WINDOW” and why it needs to be explained in museum terms. Encapsulated in this archetypal window is humanity’s propensity toward Perpetualism.

Sash window design in Paris, France circa 1630s

This only changed when an industry built on the back of lumber ran out of their precious resource and needed to find a way to stay profitable.

Planned obsolescence was their solution that would shift their attention away from WOOD as a natural resource to PEOPLE as a perpetual consumer.

Where at one time products like windows were made and sold for the value that they inherently contained, products like windows are now made as a tool to access a different renewable resource—the human race and their ability to generate a continual source of income to keep the corporations alive.

Aluminium and PVC window factory in London

Timeline of events

4000-1700 BC

The earliest windows were essentially small apertures in a wall (a ‘wind eye’). The word ‘window’ originates from the Old Norse ‘vindauga’.

vindr = wind; auga = eye

1700-500 BC

100 AD

532

1066

Builders working on a tiny Saxon church have unearthed Britain’s oldest working window. Archeologists and historians studied the workmanship of the window and have found that it dates back to before the Norman Conquest.

1200-1300

European glaziers developed a new method for displaying stained glass. Instead of marble or cement, European glaziers used strips of lead, called cames, to separate the different pieces of coloured glass. Because of the softness of the lead, the cames could be shaped into any pattern. Thus, it was possible to adorn the windows of Gothic cathedrals with detailed pictorial designs.

1250

The introduction of stone mullions (slender vertical supports that form a division between glazed areas) and a system of tracery meant that church windows could become increasingly larger.

1400

The growing cheapness of glass and the development of the fixed glazed sash resulted in an increase in the number of glazed windows in domestic buildings. Because the sashes were small, the desire for light and air was satisfied by the use of mullions and transoms to subdivide large window openings. Initially, sashes were set only in the upper portion of the window, with the lower portion still closed with shutters.

1500

By the 15th century, however, solid shutters were being replaced by hinged glazed sashes, or casements, which led to the standard use of rectangular openings in all buildings because of the ease with which the casements could be framed in them.

1670s

British architect, Robert Hooke invented the ‘sash’ window in England. In their original form, sash windows were held open by props. Wooden pegs, wedges or blocks were the only way to hold up the bottom sash until, of course, the novel idea of rope came about.

1890s

Wood windows and window moldings were commonly available through millwork companies and at lumber yards. Window and frame units were among the first building components to be made in a factory rather than built on-site.

1900s

Arts & Crafts architects and builders embraced double-hung windows, sometimes with a multi-paned upper sash, as well as casement windows. With an abundance of resources, and improved transportation, this simple, elegantly functional design became ubiquitous across the USA.